Fail Fail Again Fail Better You Fail at Failing

50 years ago, in the summertime of 1966, Samuel Beckett wrote a short story called Ping. It begins:

All known all white blank white body fixed one thou legs joined like sewn. Light rut white flooring one certain yard never seen. White walls one yard by two white ceiling i square 1000 never seen. Bare white torso stock-still only the eyes just just. Traces blurs light gray well-nigh white on white. Hands hanging palms front end white feet heels together correct angle. Light heat white planes shining white bare white body stock-still ping elsewhere.

The first time I read it, information technology reminded me of the chant-like rhythm of BBC radio'south shipping forecast: a hypnotic flow of words the meaning of which is initially utterly obscure. But persevere and patterns emerge: "moderate or adept, occasionally poor later"/"white walls", "one square 1000", "white scars". In both cases, we soon realise nosotros are inside a system of words performing very divers tasks, albeit ones only understood by initiates. Merely while fathoming the aircraft forecast can be achieved relatively apace, initiation into the organisation of words Beckett was working with in the mid-1960s is more complicated, not least because the system was corrupted, a failure, as were all the systems Beckett devised during his long career.

Beckett came to believe failure was an essential office of any artist's work, even as it remained their responsibility to try to succeed. His best-known expressions of this philosophy appear at the stop of his 1953 novel The Unnamable – " … you lot must go on. I can't get on. I'll continue" – and in the 1983 story Worstward Ho – "Ever tried. Ever failed. No thing. Effort again. Fail once more. Neglect better."

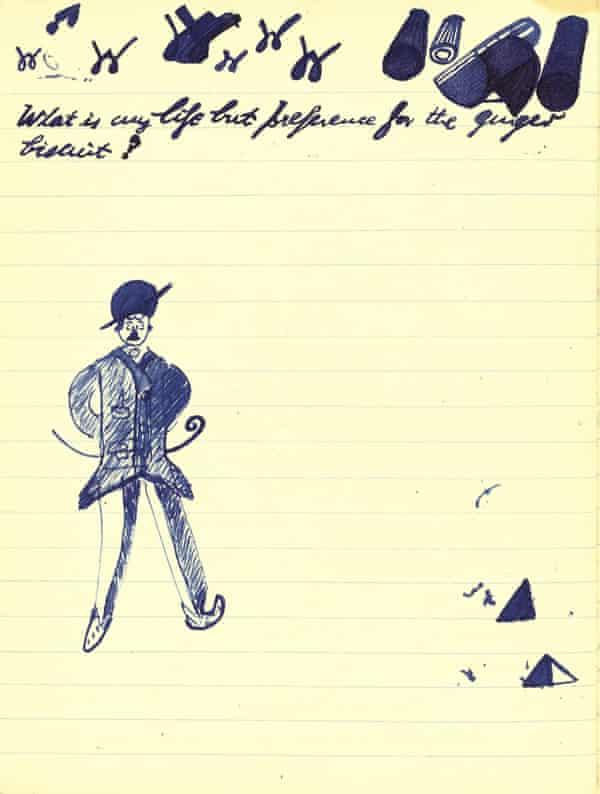

Beckett had already experienced plenty of artistic failure by the fourth dimension he developed it into a poetics. No ane was willing to publish his kickoff novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, and the book of short stories he salvaged from it, More than Pricks Than Kicks (1934), sold disastrously. The collection, which follows Beckett'southward mirror image Belacqua Shuah (SB/BS) around Dublin on a series of sexual misadventures, features moments of brilliance, is a challenging and frustrating read. Jammed with allusion, tricksy syntax and obscure vocabulary, its prose must be hacked through like a thorn bush. As the narrator comments of one character'southward wedding voice communication, information technology is "rather also densely packed to gain the general suffrage".

Throughout this period, Beckett remained very much nether the influence of James Joyce, whose circumvolve he joined in Paris in the belatedly 20s. Submitting a story to his London editor, Beckett blithely noted that information technology "stinks of Joyce", and he was right. Just compare his, "and past the holy fly I wouldn't recommend you lot to ask me what grade of a tree they were under when he put his hand on her and enjoyed that. The thighjoy through the fingers. What does she want for her thighbeauty?" with this, from Ulysses: "She let gratis sudden in rebound her nipped elastic garter smackwarm confronting her smackable woman'southward warmhosed thigh."

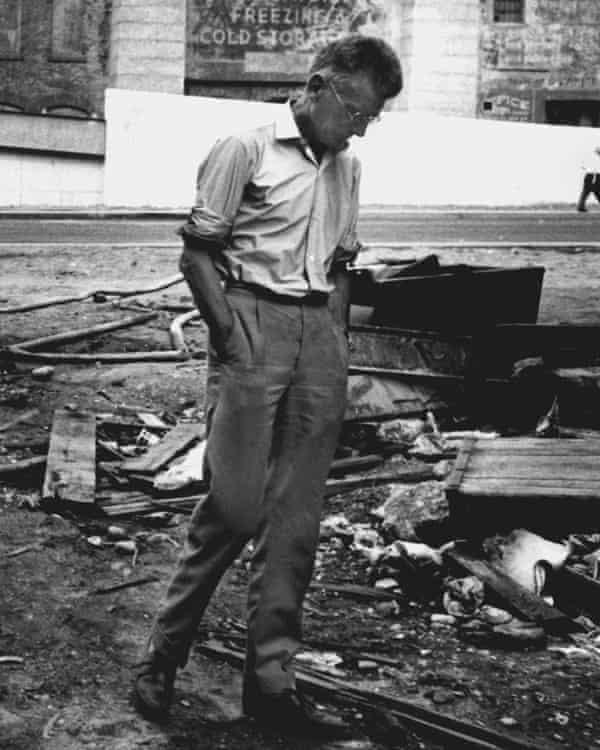

Beckett was rudderless in his late 20s and early 30s (which, thank you to the allowance he received following his begetter'due south death, he could just virtually afford to exist). He wandered for much of the 1930s, having walked out of a lectureship at Trinity College, Dublin. He returned to Paris, and so moved to London, where he wrote the novel Irish potato and underwent Kleinian psychoanalysis. He toured Germany, and in 1937 settled in Paris, where he lived until his death in 1989. During the second world state of war, he joined the resistance, fled Paris to escape arrest, and lived penuriously in Roussillon. These years of wandering and war and want influenced the character of his later work. In 1945, working at a Crimson Cross infirmary in Saint-Lô, he wrote an essay most the ruins of the boondocks, "bombed out of existence in i night", and described "this universe go provisional". Versions of this ruin strewn landscape and post-disaster environment would characterise the settings and atmosphere of much of his after work.

Although Beckett had written some poetry in French before the war, it was in its aftermath he resolved to commit fully to the language, "because in French it is easier to write without style". This decision, and his switch to the first-person voice, resulted in i of the more than astonishing artistic transformations in 20th-century literature, equally his clotted, exhaustingly cocky-conscious early fashion gave way to the strange journeys described, and tortured psyches inhabited, in the four long stories he wrote in the course of a few months during 1946. The Expelled, The Calmative and The End, and to a lesser extent Kickoff Love (which Beckett, e'er his own harshest gauge, considered junior and suppressed for many years), draw the descent of their unnamed narrators (possibly the aforementioned human being) from bourgeois respectability into homelessness and decease.

We witness a succession of evictions: from the family abode, some kind of institution, hovels and stables, basements and benches. At that place is a nagging suspicion that the initial expulsion in each story is a course of nativity, oft characterised in violent terms. (In the novel Watt, a character's birth is described equally his "ejection"; in Waiting for Godot, Pozzo says nascency takes identify "astride of a grave".) These journeys go surrogates for the journey we take through life, as Beckett perceives it: bewildered, disordered and provisional, with only brief respites from a general strife. In the terminal scene of The End, the narrator is chained to a leaking boat, his life seemingly draining away. Information technology is the monumental bleakness of works such as these (often shot through with splinters of abrupt humour), that Harold Pinter was writing of in a letter of 1954 when he called Beckett "the most courageous, remorseless writer going, and the more he grinds my nose in the shit the more I am grateful to him".

Following the four stories, Beckett reached an impasse in his writing with the Texts for Nothing (1955). Language is on the verge of breakdown in these brief, numbered pieces. The disdain in which words are held tin be summed up with the phrase "the caput and its anus the mouth", from #10. In #11 a crisis point is reached: "No, nothing is nameable, tell, no, nothing tin be told, what so, I don't know, I shouldn't accept begun." Hither the playfulness of the Three Dialogues, and the tortured backbone of The Unnamable's "I'll go along", has soured into hopelessness.

Discussing his writing in the early 60s, Beckett described a process of "getting down below the surface" towards "the authentic weakness of being". Failure remained unavoidable because "[w]hatever is said is so far from the experience" that "if you actually get down to the disaster, the slightest eloquence becomes unbearable". Thus, the narrowing of possibilities that the Texts for Goose egg describe leads into the claustrophobia of the "closed infinite" works of the 1960s. Commencement with the novel How Information technology Is (1961), told by a nameless man lying in darkness and mud, and continuing with All Strange Abroad (1964), Imagination Dead Imagine (1965) and the aforementioned Ping, Beckett describes a serial of geometrically distinct spaces (cubes, rotundas, cylinders) where white bodies lie, or hang, singly or in pairs. Beckett had reread Dante, and something of his Hell and Purgatory characterises these claustrophobic spaces. The linguistic communication with which they are described is so fragmented that it is difficult to orient ourselves: we are in a organization of words where multiple paths of meaning co-operative from every sentence, non on the level of interpretation but of basic comprehension. Accept for example the opening line of Imagination Expressionless Imagine:

No trace anywhere of life, you say, pah, no difficulty there, imagination non dead yet, yes, dead good, imagination dead imagine.

Does the "y'all say" await back to "No trace anywhere ", or does it anticipate "pah, no difficulty at that place"? As Adrian Hunter writes:

What punctuation in that location is has the effect not of assisting interpretation but of further breaking downward whatever chain of pregnant in the language. A uncomplicated orientational phrase like "you say" hovers uncertainly betwixt its commas; instead of securing the spoken language acts that surround it, it operates as a kind of revolving door by which one both exits and enters the various semantic fields in the passage.

In Beckett'southward next work, Enough (1965), he abased both the first person and the comma (only a handful are found in all of his later prose), his sentences condign terse as bulletins, brusque afterthoughts ("modifier after modifier", in ane description) typically consisting of mono- or disyllabic words, that try – and fail – to clarify whatsoever epitome or awareness he is attempting to express. Hugh Kenner has written memorably of this stage that Beckett:

Seems unable to punctuate a sentence, let alone construct one. More than and more securely he penetrates the heart of utter incompetence, where the simplest pieces, the merest iii-word sentences, fly apart in his hands. He is the non-maestro, the anti-virtuoso, habitué of non-class and anti-affair, Euclid of the night zone where all signs are negative, the comedian of utter disaster.

Kenner'southward evaluation echoes Beckett'southward own words from a 1956 New York Times interview, when he contrasted his approach with that of Joyce: "He's disposed towards omniscience and omnipotence as an artist. I'1000 working with impotence, ignorance". The impasse reached in the Texts for Aught continues in a story like Lessness (1969), which really runs out of words: the 2d half of the text simply duplicates the first half with the words reordered, leaving us, in JM Coetzee's description, with "a fiction of net zip on our hands, or rather with the obliterated traces of a consciousness elaborating and dismissing its ain inventions".

Strategies like these make navigating Beckett's piece of work even more challenging for the reader, to the degree that some critics decided pointlessness was its very indicate. In the case of Ping, this position is strongly rebutted in a 1968 essay by David Gild. While acknowledging that it is "extraordinarily difficult to read through the entire piece, brusk as information technology is, with sustained concentration", the words before long beginning to "slide and blur before the eyes, and to echo bewilderingly in the ear", he concludes that "the more closely acquainted we become with Ping, the more certain we become that information technology does matter what words are used, and that they refer to something more specific than the futility of life or the futility of art."

Beckett'southward closed-space stage culminates in The Lost Ones (1970), a nightmarish vision of a sealed cylinder within which "fugitives" circulate until futility or death overcomes them. The Lost Ones updates Dante into what i reviewer called "the art of a gas-sleeping accommodation globe". It is written at an anthropological remove, the cylinder described in punishing detail, and at punishing length. For all the clarity of its language compared with Ping or Lessness, information technology is the near forbidding of his shorter prose works.

Information technology was almost a decade before any more than meaning short prose emerged, merely when it did another shift had taken identify. The terrifying closed spaces were complanate and gone, replaced by the twilit grasslands of Stirrings Still (1988), or the isolated cabin, "zone of stones" and ring of mysterious sentinels in Ill Seen Sick Said (1981). Language remains problematic, but a level of acceptance has been reached. The phrase "what is the wrong word?" recurs in Sick Seen Ill Said, as if to say: "Of course language is insufficient, but approximation is meliorate than nix":

Granite of no mutual variety assuredly. Blackness as jade the jasper that flecks its whiteness. On its what is the incorrect word its uptilted confront obscure graffiti.

In these stories, written in the final decade of Beckett'due south life and in which stylised settings blend with autobiographical material, ofttimes from his childhood, he seems to deliver u.s.a. to the source of his creativity, to the moment where an idea sparks in the witting heed. The terrain and structures of Ill Seen Ill Said seem to come into existence at the very moment we read them. "Conscientious," he writes, tentatively bringing his creation into the world as if guarding a friction match flame:

The two zones form a roughly circular whole. As though outlined by a trembling mitt. Diameter. Careful. Say one furlong.

It is an irony of Beckett's posthumous reputation that his plays are now far meliorate known than his prose, although he considered the latter his primary focus. That he wrote some of the greatest short stories of the 20th century seems to me an uncontroversial merits, notwithstanding his work in this genre is insufficiently obscure. Partly this is a problem of classification. Equally one bibliographical note puts information technology: "The distinction between a discrete short story and a fragment of a novel is not e'er articulate in Beckett's work." Publishers have colluded in this confusion: as evidence of the British phobia of brusk stories goes, it's hard to crush John Calder's blurbing of the 1,500-word story Imagination Expressionless Imagine every bit "peradventure the shortest novel ever published". Then besides there are examples such as William Trevor'south exclusion of Beckett from the 1989 Oxford Book of Irish Short Stories for the nonsense reason that he expressed his ideas "more skilfully in another medium", or Anne Enright excluding him from her ain pick for Granta.

I suspect the real trouble with Beckett'due south short fiction is its difficulty, and that his greatest achievements in the form do non comply with what some gatekeepers suppose to be the genre's defining traits. Unfortunate as the resulting fail might be, this is a fitting position to exist occupied by a writer who consistently struggled to develop new forms. If the history of the curt story were mapped, he would belong in a distant region. The isolation would not matter. "I don't discover solitude agonising, on the opposite", he wrote in a letter of 1959. "Holes in paper open and accept me fathoms from anywhere."

mcclurecoursentand1937.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2016/jul/07/samuel-beckett-the-maestro-of-failure

0 Response to "Fail Fail Again Fail Better You Fail at Failing"

Post a Comment